As the leading quarterback in Texas, Gov. Abbott has shown a repeated tendency to fumble the ball as Covid-19 infections have surged in Texas. Instead of following the advice of the nation’s top experts on controlling the spread of Covid-19, Gov. Abbott has opted instead to place the lives of many Texans at risk by following the GOP party line of opening the Texas economy. The governor was warned repeatedly by the commissioners in Dallas and Harris counties that Texas was not ready to re-open its businesses, but their advice was ignored and sometimes ridiculed by Abbott. The consequences of this oversight have been devastating. Not surprisingly, the Texas Democratic Party described the governor’s strategy as “reckless.” [1]

After the governor authorized the re-opening of Texas businesses, Travis, Harris and Dallas counties experienced record high cases for two weeks, surging to 4,739 on Thursday morning (June 25th) and tripling since Memorial Day.[2] These three counties are now reviving plans for temporary hospital facilities to prepare for overwhelmed hospitals. Gov. Abbott finally acknowledged that the opening of businesses was perhaps a bit premature and should be “paused” to ease the burden on Texas hospitals. As a result, he issued an executive order to close all bars in Texas and reduce the restaurant capacity to 50 percent. Unfortunately, a definitive action to mandate the use of face masks in public – considered highly effective in slowing the spread of Covid-19 — did not emerge.

As the governor recently explained: “The last thing we want to do is go backwards and close down businesses…the pause will help our state corral the spread.” Indeed, the Covid-19 spread does not pause simply by closing business establishments but will continue to seek other victims, especially those that are unprotected by face masks, meeting or working indoors in groups, and persons with existing comorbidities.

The Covid-19 statistics in Texas are quite grim: 137,624 reported cases; 2,324 fatalities, and 59,018 active cases.[3] How many more lives need to be sacrificed before Governor Abbott decides to more aggressively slow the spread of Covid-19? Interestingly, while Governor Abbott continues to fumble with his hit-or-miss strategy, other states like New York, New Jersey and Connecticut that have more successfully controlled the spread of Covid-19 are requiring a 14-day quarantine for visitors from states like Texas with big outbreaks of the virus. [4]

Impact on Communities of Color in Texas

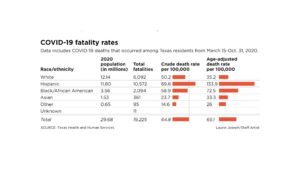

The consequences of these poor judgements by Governor Abbott have been compounded by two other factors: the common victims of Covid-19 and the state’s demographic composition. Various studies have confirmed that Covid-19 infections and mortalities are disproportionately impacting Blacks [5] and Hispanics [6] in communities throughout the U.S. For example, an analysis of recent Dallas County Covid-19 cases by UT Southwestern Medical Center revealed that Hispanics comprised 60 percent of all new cases while their county population was 40 percent. [7]

Various explanations have been proposed to explain the heightened vulnerability of Blacks and Hispanics to Covid-19, including the types of jobs held (i.e., factories, food service); living in crowded situations with less options for social distancing; lack of Covid-19 testing; and skepticism about medical doctors.

The urgency of acting more quickly in Texas is compounded by the fact that Hispanics (39.2%) and Blacks (11.7%) collectively comprise half (50.9%) of the state’s population [8] — a demographic reality suggesting that the consequences of Covid-19 for these two segments of the Texas population are likely to be more severe as a result of Abbott’s continued failure to follow the advice of health experts.

To this point, there is evidence that Blacks and Hispanics are struggling more than whites and Asians to meet important daily needs since the pandemic started. In a major effort to help the nation monitor post-Covid-19 experiences on a weekly basis, the Census Bureau along with several federal agencies began surveys with samples of residents in 15 metropolitan areas and has made the results of these surveys available to the public.[9] The survey, provided in English and Spanish, was designed as a timely and periodic measure of the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) on the following topics:

- Employment status

- Food security

- Housing security

- Education disruptions

- Physical and mental well-being

Our analysis of the 1,586 surveys completed in the Dallas/Ft. Worth metropolitan area during the week of June 11, 2020 revealed the following race-ethnic differences on three of the topical areas:

· Food security: Hispanics (16.9%) and Blacks (15.5%) were more likely than whites (3.3%) and Asians (3.5%) to state that they were not at all confident about their ability to afford the kinds of food that they needed for the next four weeks. Hispanics (12.4%) were more likely than whites (5.1%), Blacks (1.9%) and Asians (5.0%) to agree that it was often true that their children were not eating enough because they could not afford enough food. Hispanics (15.8%) and Blacks (16.0%) were more likely than whites (6.5%) and Asians (2.3%) to agree that they sometimes/often did not have enough food to eat during the past seven days.

· Employment status: Hispanics (65.4%) and Blacks (51.9%) were more likely than whites (43.1%) and Asians (32.9%) to state that they or someone in their household had experienced a loss of employment income since March 3, 2020. In addition, Hispanics (48.5%) and Blacks (45.4%) were more likely than whites (24.0%) and Asians (17.8%) to state that they or someone in their household expected a loss of employment income over the next four weeks.

· Housing security: Hispanics (27.9%) and Blacks (30.8%) were more likely than whites (9.2%) and Asians (15.8%) to state that they had no confidence/slight confidence that their household would be able to pay their next rent or mortgage payment on time.

Absence of a Safety Net

For Blacks and Hispanics, surviving the pandemic is analogous to avoiding a torpedo that has already been launched given their history of comorbidities, the jobs that they hold, and other limitations. Their dilemma is further amplified by the absence of a safety net for healthcare, economic and social services. Hispanic immigrants are especially vulnerable to the consequences of Covid-19 because they are:

· Unable to participate in Medicare or Medicaid;

· Unable to obtain Social Security benefits despite the millions in contributions that employees make annually;

· Not eligible to obtain food stamps;

· Not eligible for stimulus payments due to the pandemic;

· Not eligible for unemployment benefits; and

· Often working in hazardous environments since their employers are infrequently inspected by OSHA for compliance with Covid-19 standards.[10]

Making matters worse, the State of Texas has joined the Trump administration in requesting that the U.S. Supreme Court end Obamacare – a cruel action that will leave many Texans without the care that they need to recover from the devastation caused by the pandemic.

Although some reports have indicated that the Covid-19 death rates are not increasing along with increasing infection rates, we should not take any comfort with this trend because race-ethnic information is often missing from death certificates. The actual mortality rates for Blacks and Hispanics could be much higher than currently reported. [11]

A Different Approach to Stimulating the Texas Economy

The irony in Governor Abbott’s quest to stimulate the Texas economy is not lost here. Would it not make better sense to more aggressively stop the spread of Covid-19, give residents the opportunity to restore their health and return to jobs at businesses that have been certified as safe from Covid-19 exposure? Texas Hispanics and Blacks, for example, comprise a large segment of the state’s workforce in various industries. Moreover, aggregate household income in 2018 — $184 billion for Hispanics [12] and $73 billion for Blacks [13] – represents a substantial contribution to the Texas economy. The increasing loss of Hispanics and Blacks from the Texas workforce due to Covid-19 infections and mortalities would substantially slow down the economy and possibly negate the progress expected by Abbott in re-opening business establishments.

In the absence of a safety net, it might be a good idea for private corporations in Texas to collectively create a special fund that could be used to support vulnerable groups like Blacks and Hispanics who need financial support during this difficult period. After all, the substantial consumer spending of these two segments has contributed to the profitability of many Texas retailers and manufacturers, such as Walmart, Mission Foods, Fiesta Supermarkets, Kroger, H-E-B, Sherwin-Williams, Home Depot, and various others. The contributed funds could be distributed to Black and Hispanic families during this difficult period with the goal of maintaining their good health; returning to work in businesses that the state has certified as safe and free of Covid-19 exposure; and continuing their consumer spending at Texas businesses. This makes more sense – scientifically and economically.

Final Message to Governor Abbott

The following recent quote in The Washington Post accurately summarizes the failure in leadership by Governor Abbott and other leaders that are following the same Covid-19 strategy:

“A record surge in new cases is the clearest sign yet of the historic failure in the United States to control the virus – exposing a crisis in governance extending from the Oval Office to state capitals to city council.” (Page 2) [14]

It is especially perplexing that the pandemic battle in Texas has been presented in news stories as an ongoing fight between the Governor and judges in Dallas and Harris counties – a pattern that has muted the voices of the Hispanic and Black communities where the virus is likely to have the most devastating impact. The media should assume more responsibility for including the voices of Hispanic and Black leaders in Texas who are supporting the scientific solution that has been advocated by Judge Jenkins and Judge Hidalgo. They could use some help.

Governor Abbott, you have a responsibility to protect the lives of all Texans without delay, especially during a pandemic. You should forget about party loyalty and act decisively according to the advice of the nation’s health experts. In case you forgot, start by ordering the following:

· Mandate the use of face masks in public and impose fines on people that refuse to obey the law;

· Discipline public officials that refuse to comply with the law;

· Re-institute the stay-at-home order;

· Close dining options at restaurants and allow only take-out or delivery;

· Prohibit the use of group meetings in public facilities (i.e., conventions) and encourage churches to conduct virtual masses instead of masses attended by their membership;

· Allow schools to open only if they are required to use face masks and adhere to social distancing guidelines. Older or more vulnerable teachers should be assigned to teach online classes;

· Authorize more financial resources to expand the state’s testing capabilities to avoid the long lines and waiting periods for residents who are becoming increasingly motivated to measure their Covid-19 exposure;

- Launch a public relations campaign that shows all public officials wearing a mask and reminding Texas residents that wearing a mask is required by law and not an option. Going forward, the campaign should avoid using the familiar phrase “Wearing a face mask is a good idea” and replace it with a clearer message like “Wearing a face mask is a life or death issue – obey the law;” and

- Lastly, consider placing Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins and Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo to lead a Covid-19 commission composed of the state’s top healthcare experts to manage the state’s Covid-19 strategy going forward. Both judges have been more forceful in warning Governor Abbott against re-opening Texas businesses and showing the appropriate respect for science to protect the health of Texas residents. Importantly, the unbiased and more objective management of the Covid-19 strategy by this commission should ensure that political considerations are removed from future decisions related to the distribution of Covid-19 treatments and vaccines as they become available.

End Notes

[2] Champagne, S.R. (2020 June 25). Ibid.

[8]Census Bureau (2018).

ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, Table DP05, 2018 5-Year Estimates. Accessed at

www.data.census.gov.

[13] Census Bureau. Aggregate income in the past 12 months – Hispanic households. Table B19313.

Accessed at: www.data.census.gov

[14] Hawkins, D., Birnbaum, M., Kornfield, M., O’Grady, S., Copeland, K. Lati, M. and Sonmez, F. (2020 June 29). Arizona, Florida, Texas are latest coronavirus epicenters. The Washington Post. Accessed at:

http s://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/28/coronavirus-live-updates-us/